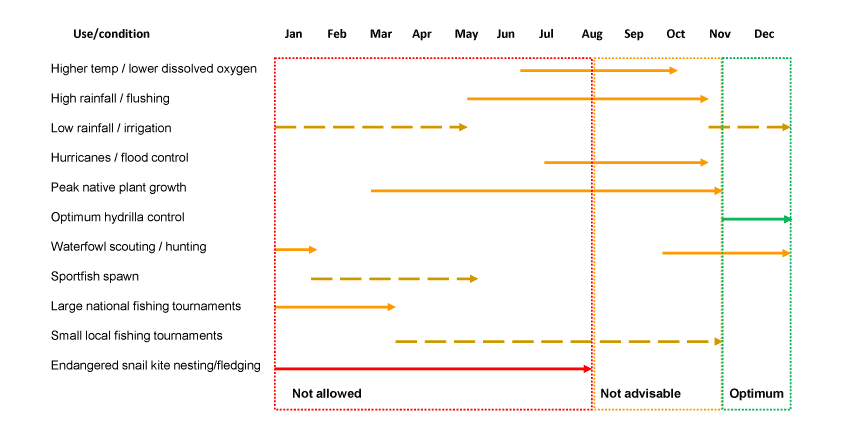

Large-scale hydrilla control considerations for Lake Toho

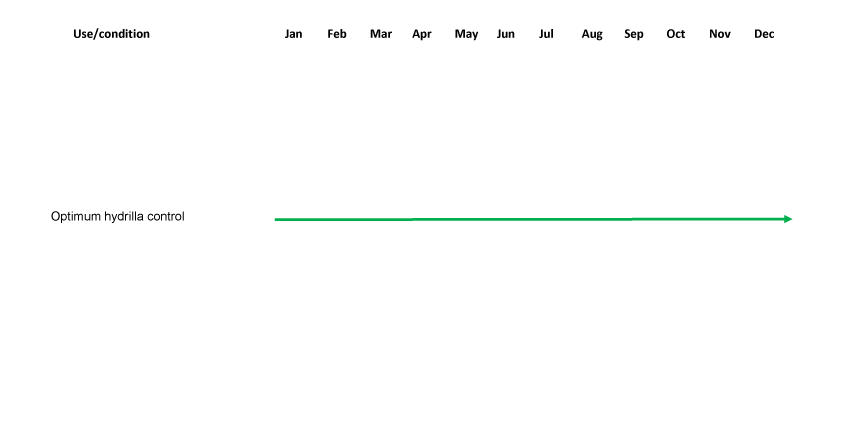

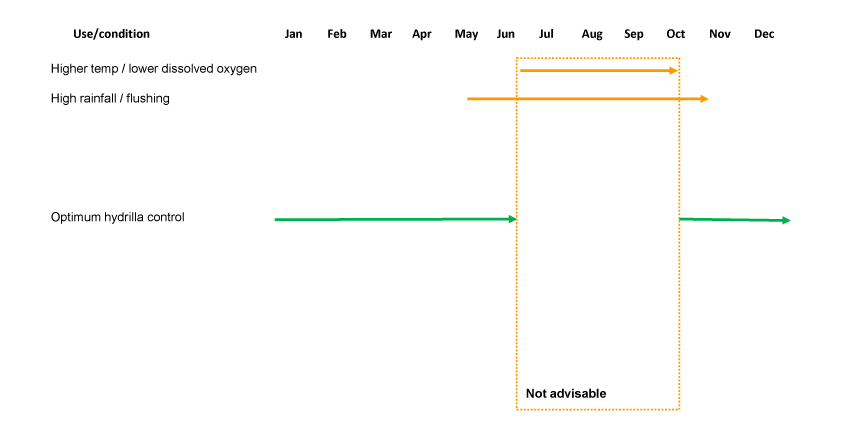

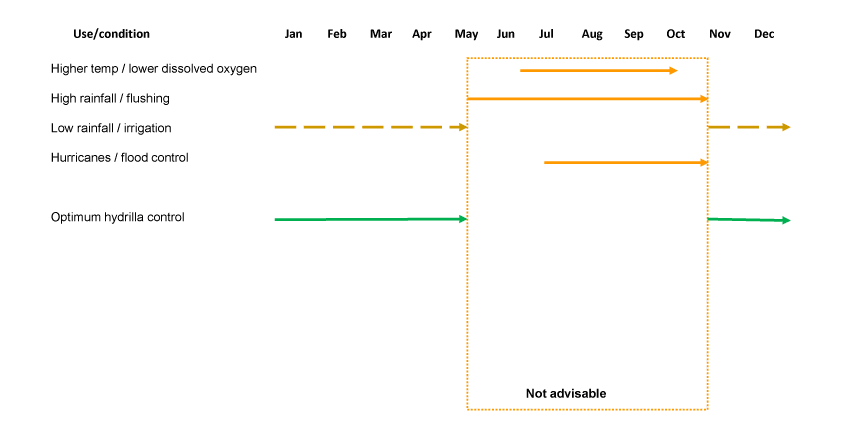

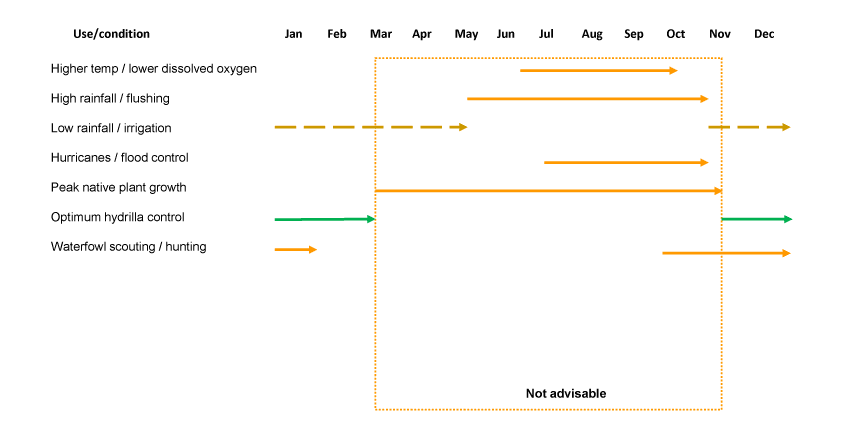

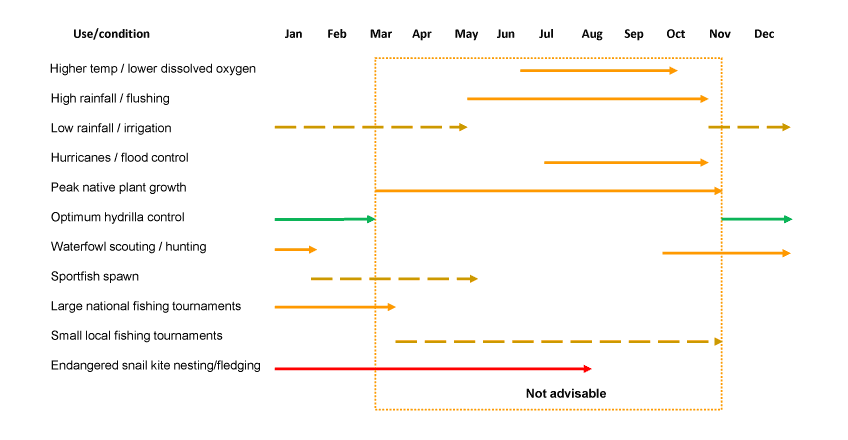

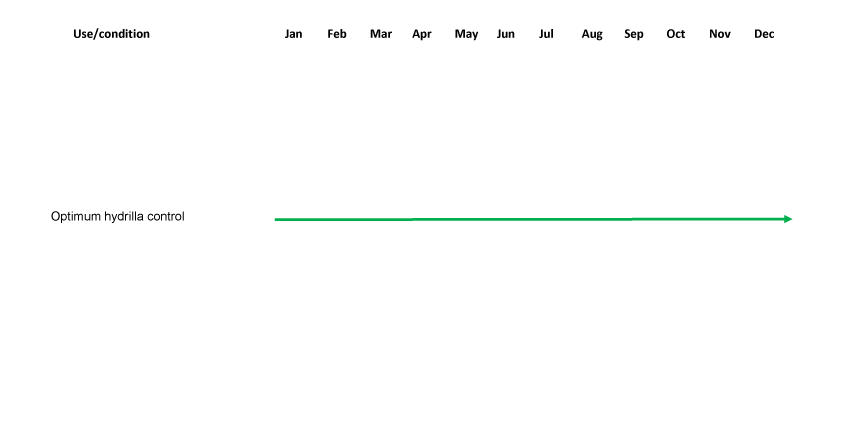

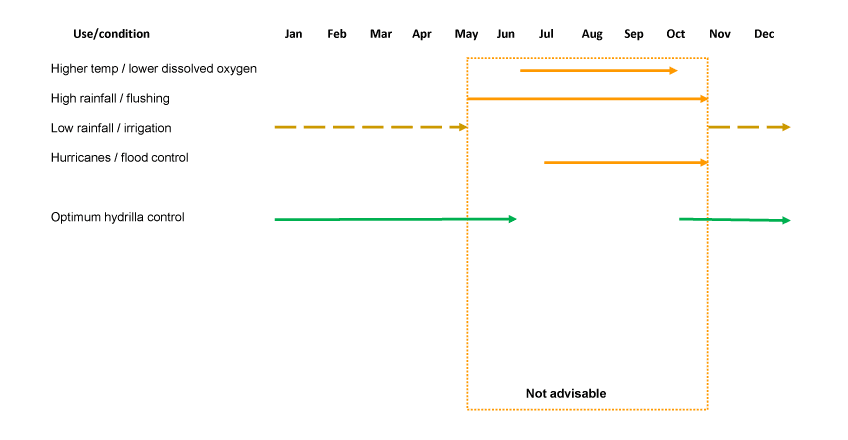

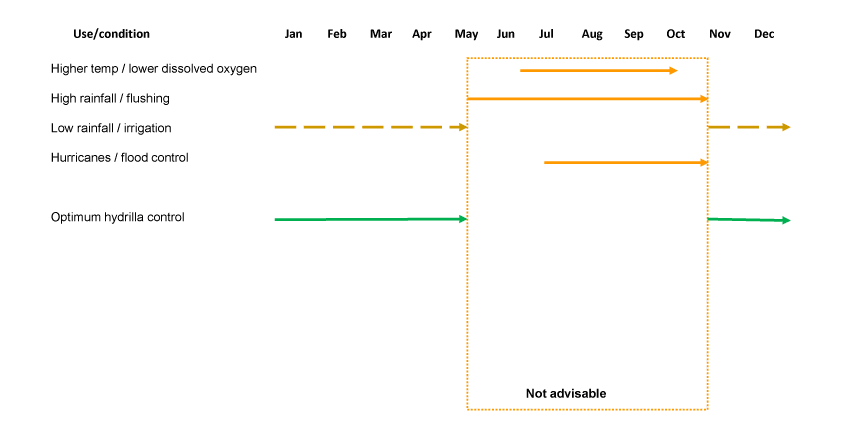

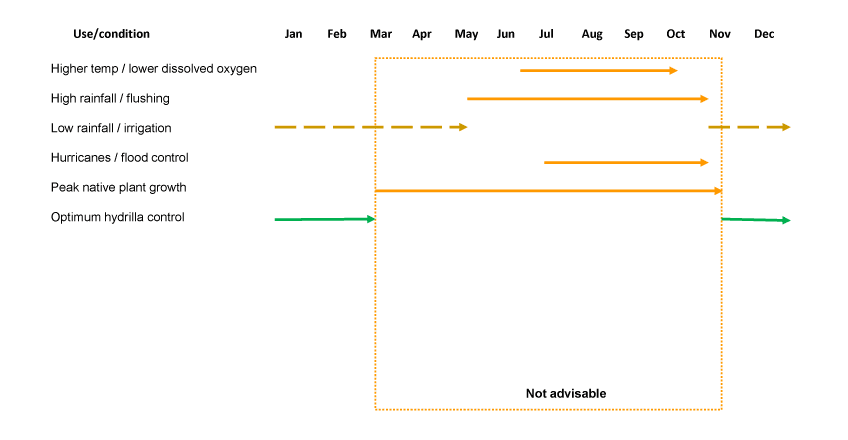

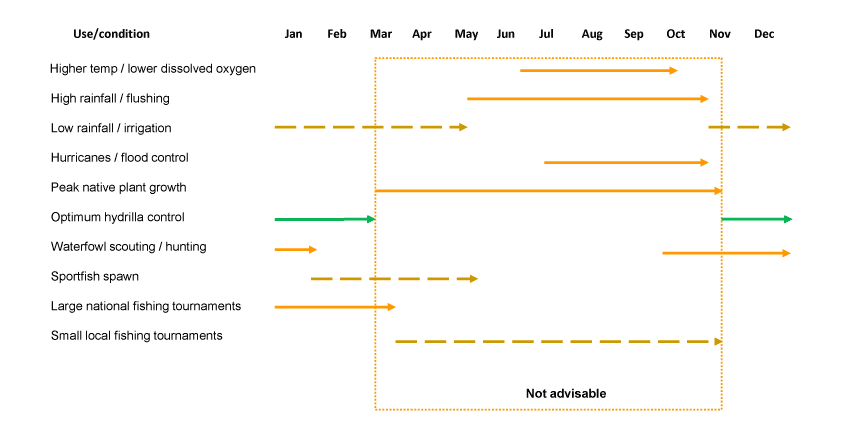

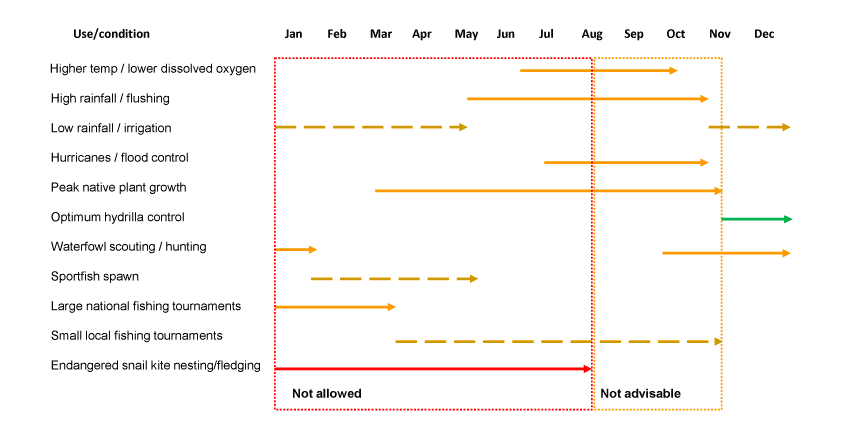

One would think we could conduct large-scale hydrilla management any time during the year thanks to Florida’s pleasant subtropical climate. As it turns out, there are many considerations and factors involved and limited opportunities.

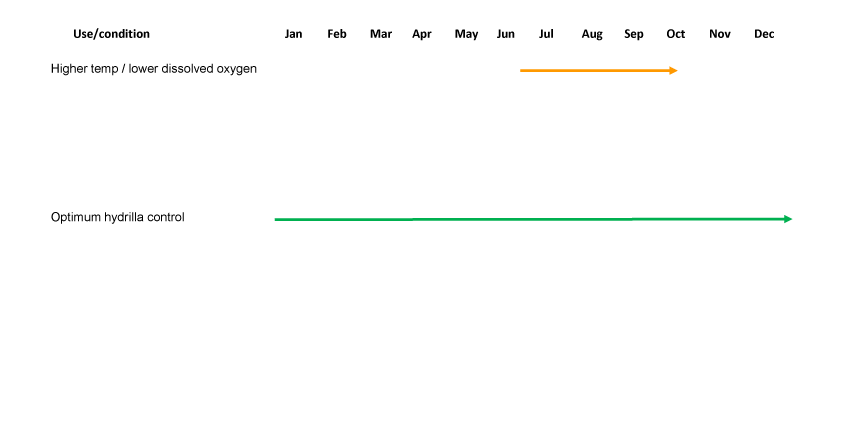

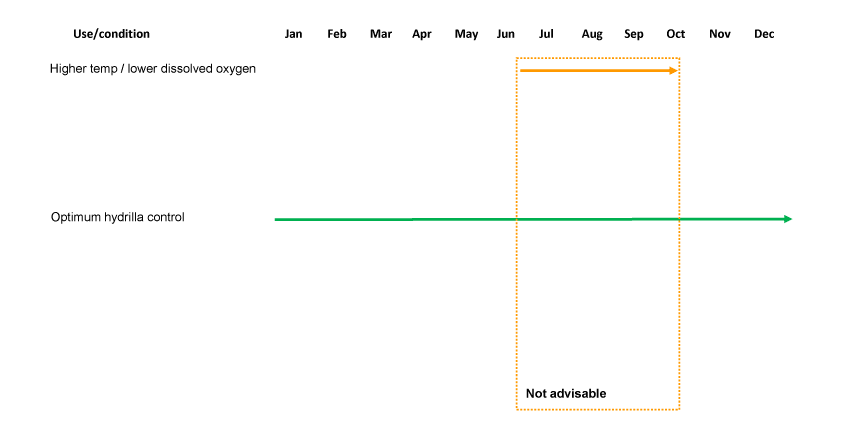

CONSIDERATION: Water temperature

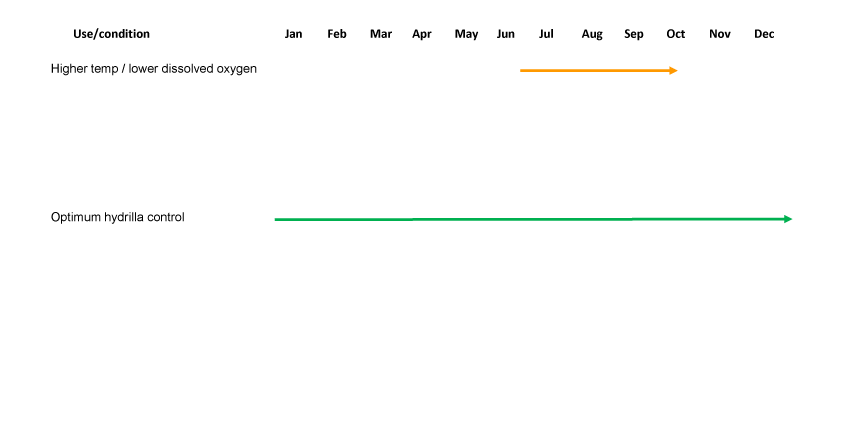

Water temperature must be considered when planning large-scale hydrilla control. As temperatures rise in Lake Toho each Spring, the water’s ability to hold dissolved oxygen is reduced. Dissolved oxygen is important for fish and other gilled organisms to breathe and for support of microbial decomposition of dead and decaying vegetation. Controlling large-stands of hydrilla too quickly during hot summer months may reduce dissolved oxygen below levels necessary for fish survival.

However, leaving large masses of hydrilla in Lake Toho during hot summer months may also lead to oxygen depletion. While hydrilla generates oxygen as part of the photosynthesis process during daylight hours, it consumes oxygen during respiration at night and during cloudy days. Warm water temperatures increase oxygen problems–especially after several consecutive cloudy days.

CONSIDERATION: Water temperature

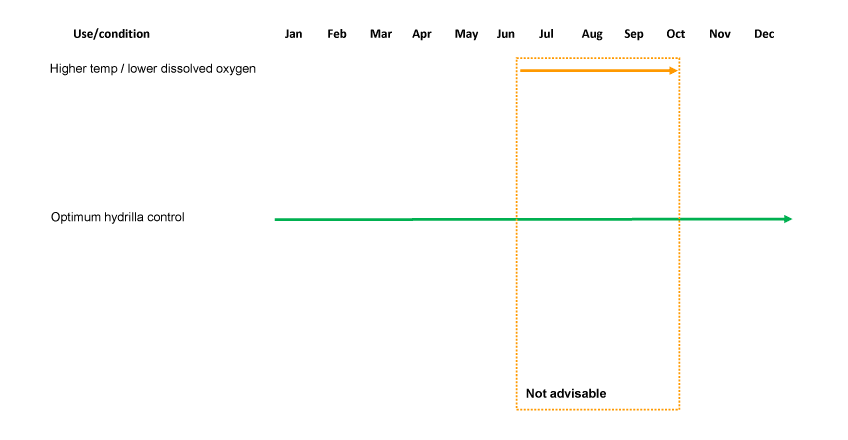

Therefore, large-scale hydrilla control, especially with fast acting contact type herbicides, is not advisable during hot summer months.

CONSIDERATION: Water temperature

Warm water temperatures during summer months reduce the opportunities for optimum hydrilla control.

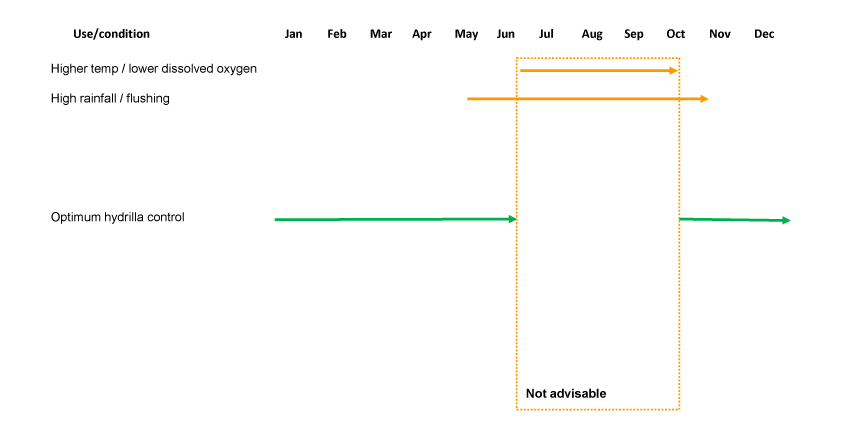

CONSIDERATION: Rainfall – increased water flow – flushing

Large-scale herbicide control in Lake Toho usually entails a significant financial investment, often exceeding $1 million. An herbicide dose must remain in contact with hydrilla for several days for contact-type herbicides, and for several months for systemic herbicides. Rainfall typically increases in the Lake Toho watershed from May through early November coinciding with tropical storms and hurricanes–making it especially challenging to treat hydrilla effectively before herbicides are diluted or flushed out of the control zone in this flow-through reservoir.

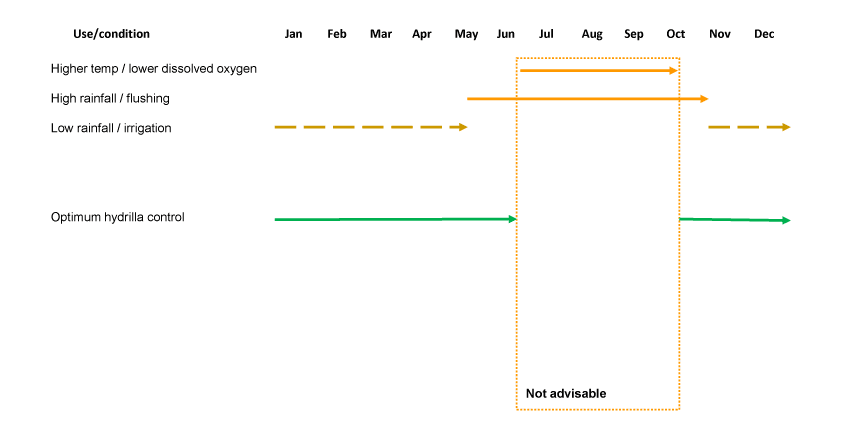

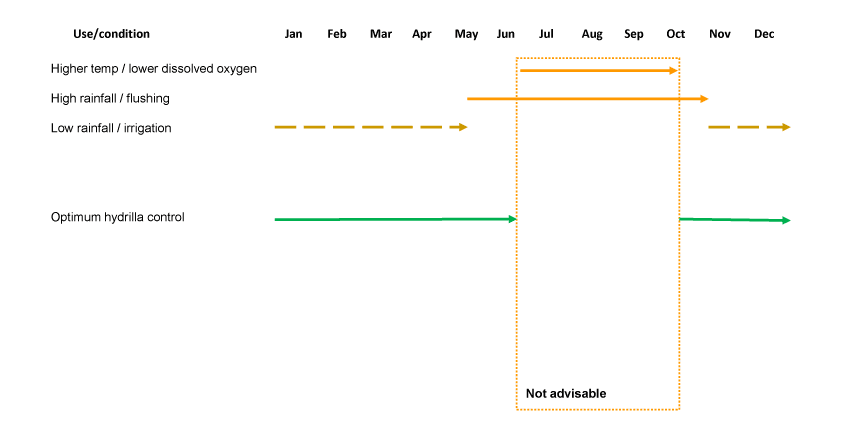

CONSIDERATION: Rainfall – irrigation

Generally, rainfall is much lower in the Lake Toho watershed during November through April making this cool water, low flow period more suitable for large-scale hydrilla control. Crop irrigation needs, from Lake Toho water, are generally higher during the dry winter and spring months. Although Lake Toho is used somewhat for irrigation, large-scale hydrilla management is not heavily influenced by this.

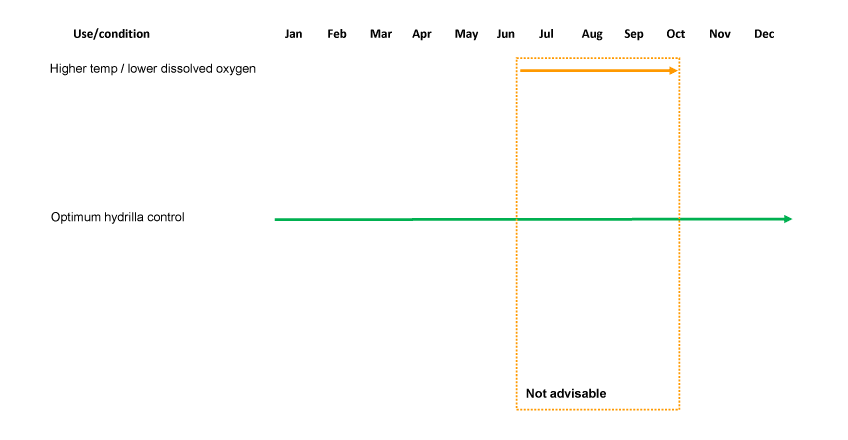

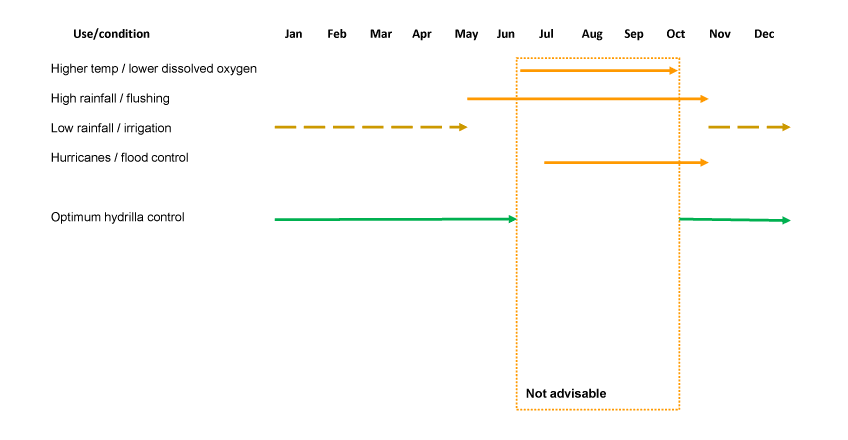

CONSIDERATION: Hurricanes – flood control

In addition to the flushing effect from rainfall, managers are aware that hydrilla must be under control before hurricane season so dense stands of hydrilla do not impede water flow and diminish the flood control capacity of the system during a storm. Hurricane season is generally more active from June through October.

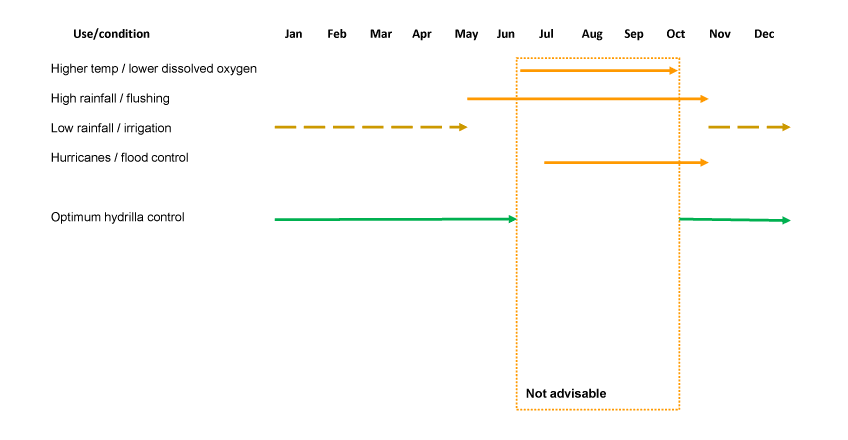

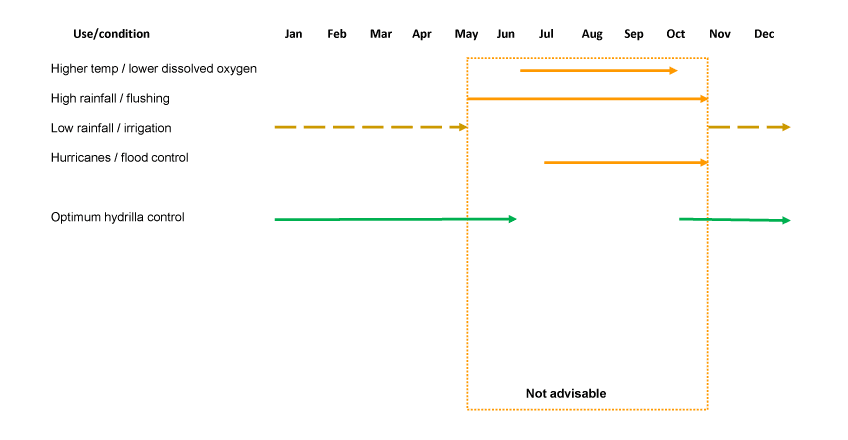

CONSIDERATION: Hurricanes – flood control – rainfall – water flow – flushing

Hydrilla must be controlled to meet flood control requirements for Lake Toho before hurricane season. However, initiating large-scale hydrilla control on Lake Toho from the onset of the rainy season through the end of hurricane season is not advisable due to flushing action that may occur from "normal" seasonal rainfall.

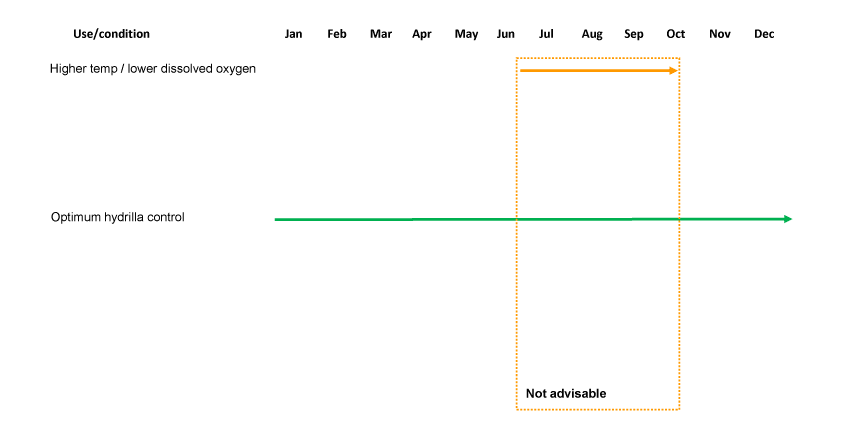

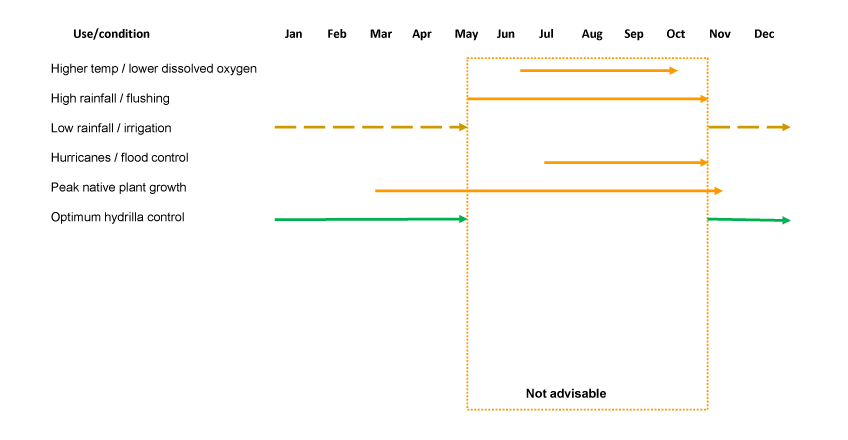

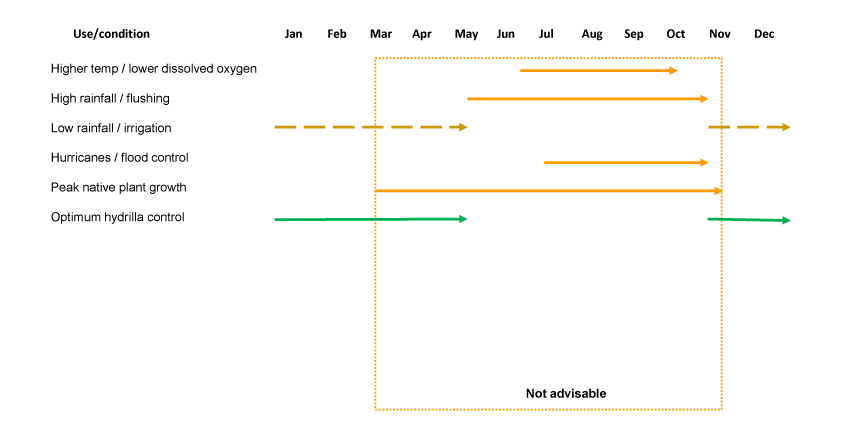

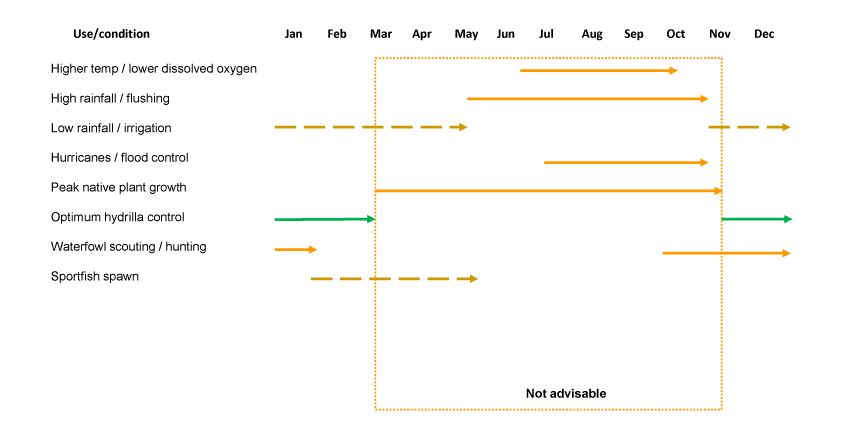

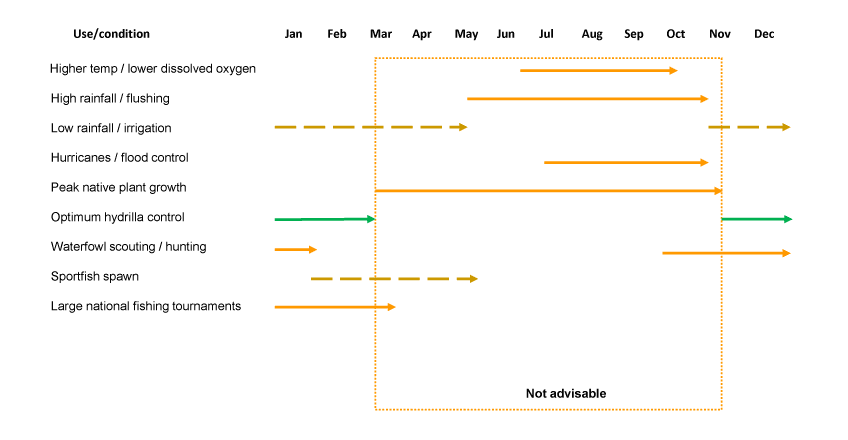

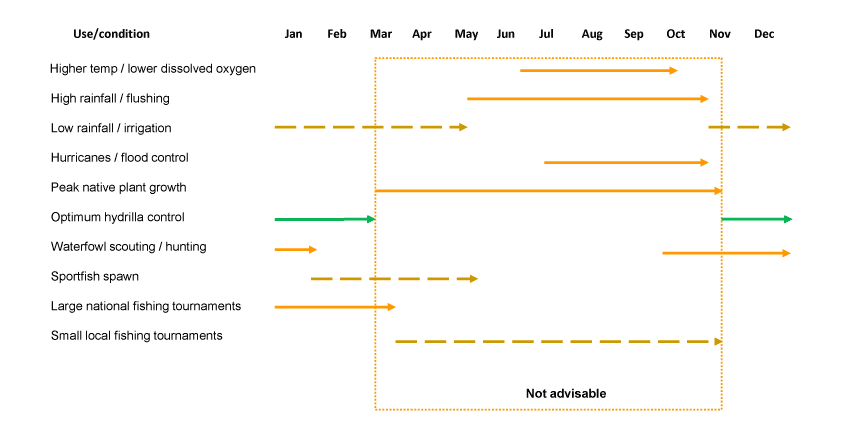

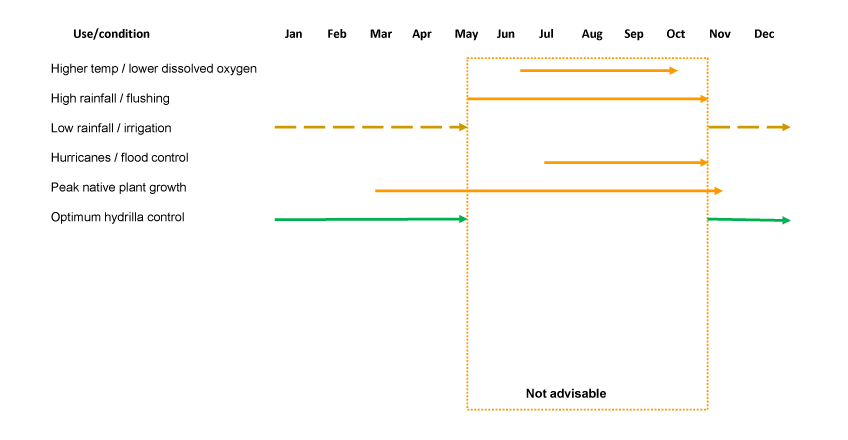

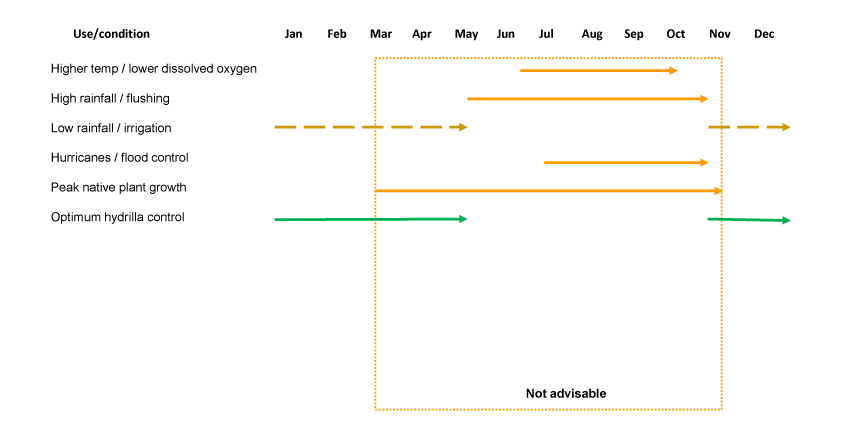

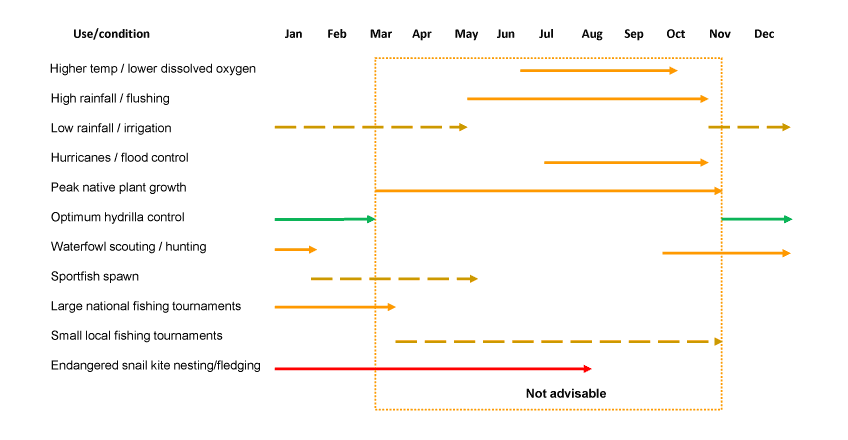

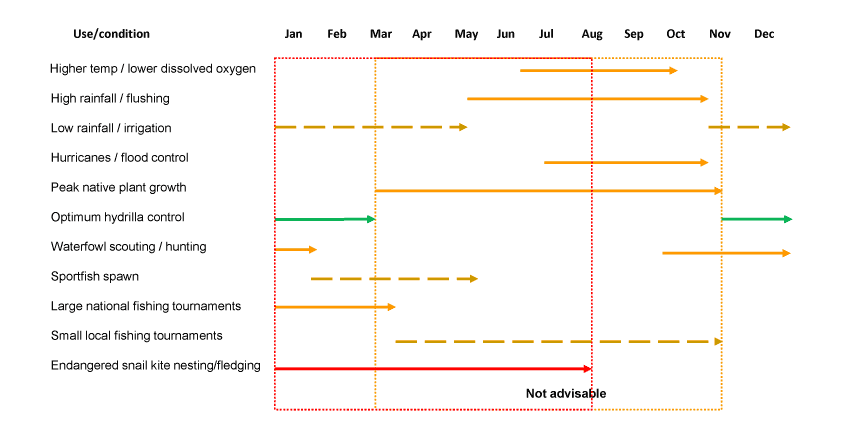

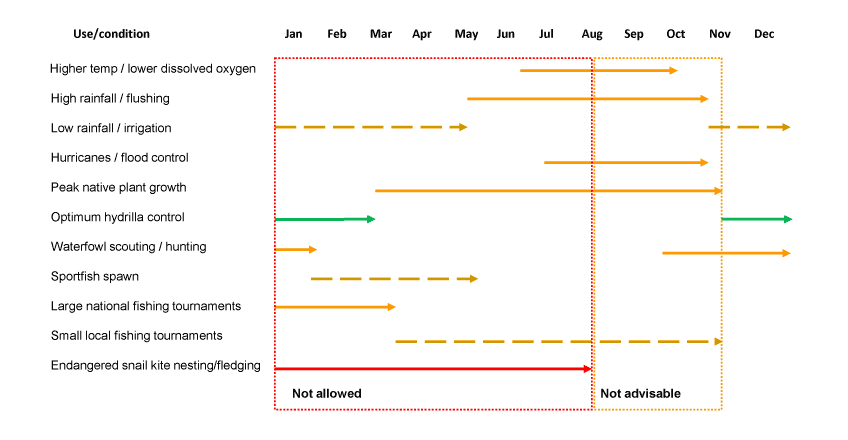

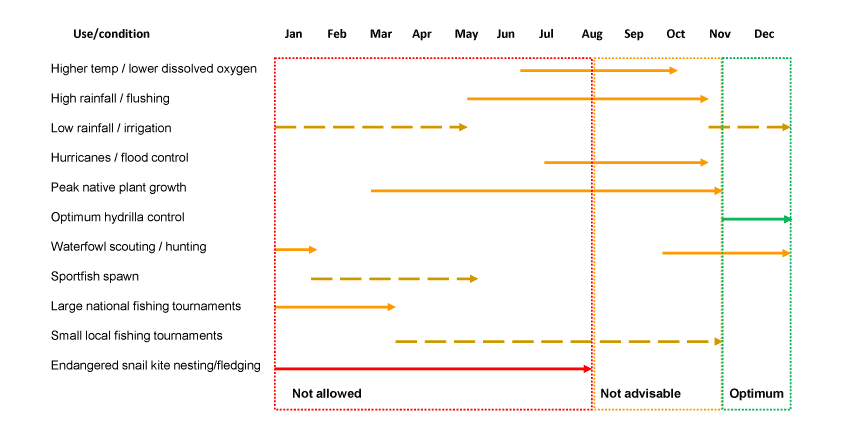

Notice: the “Not Advisable” box in the graphic above is increasing in size and the opportunity for optimum hydrilla control is decreasing.

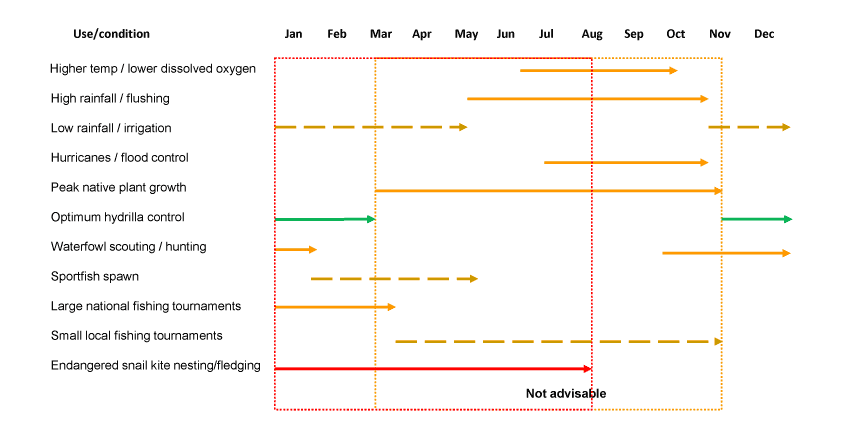

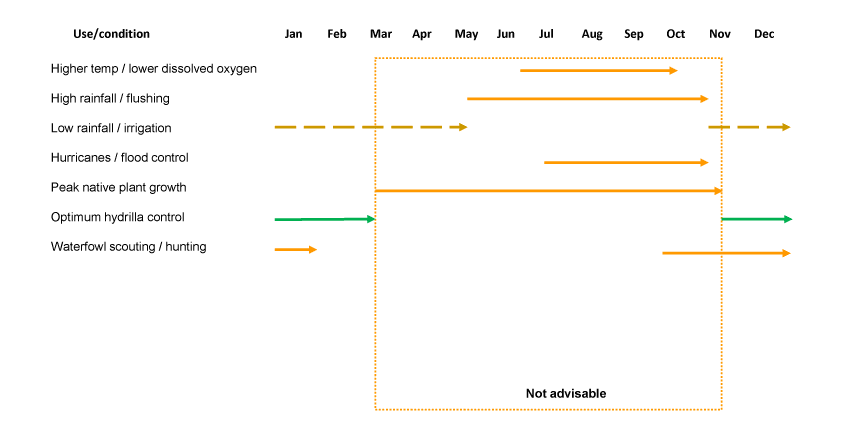

CONSIDERATION: Plant growth

Hydrilla continues to grow later in the fall and begins active growth earlier than most native submersed aquatic plants in the spring. Managers commonly rely on this growth trait to selectively control hydrilla in winter months since plants must be actively growing to “take up” herbicides from the water column. This creates a dilemma:

CONSIDERATION: Plant growth

Plant managers want to conserve or enhance native plant communities as much as possible. However, as native plants come out of winter dormancy and begin active growth, they may become more susceptible to herbicides applied for hydrilla control. Therefore, it is not advisable to conduct large-scale hydrilla control during spring through early fall months when native submersed plants are most vulnerable.

Opportunities for optimum large-scale hydrilla control are further reduced and the "not advisable" time frame increases.

CONSIDERATION: Plant growth

CCONSIDERATION: Waterfowl

Lake Toho is frequently used for waterfowl hunting in addition to its world-renowned fishery. Waterfowl scouting begins as early as late September and waterfowl hunting seasons extend through January.

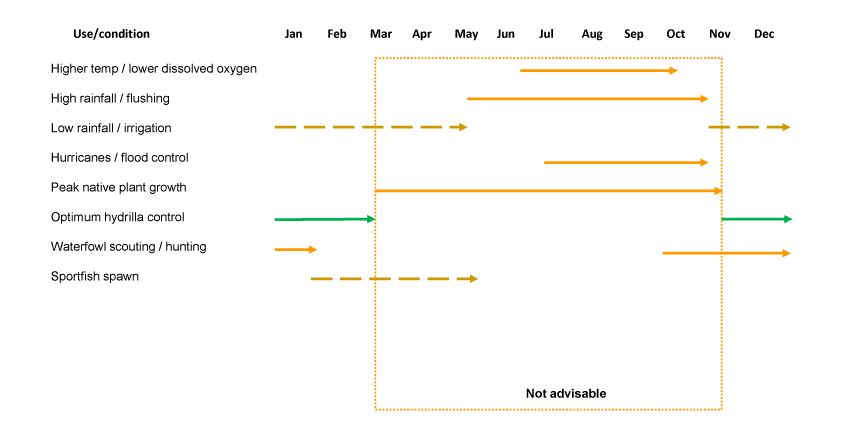

CONSIDERATION: Sportfish

Spawning season for sportfish depends on the fish species and water temperature but it generally extends from late January through May.

CONSIDERATION: Sportfish

Large national fishing tournaments generally are held during the winter months on Lake Toho.

CONSIDERATION: Sportfish

Dozens of smaller local tournaments are held mostly in late spring through the fall.

CONSIDERATION: Endangered species

Hydrilla managers are acutely aware that endangered Everglades snail kites and their primary prey, apple snails, nest throughout the littoral zone of Lake Toho. Kites begin courtship and nesting behavior in January and nests may be occupied as late as August.

CONSIDERATION: Endangered species

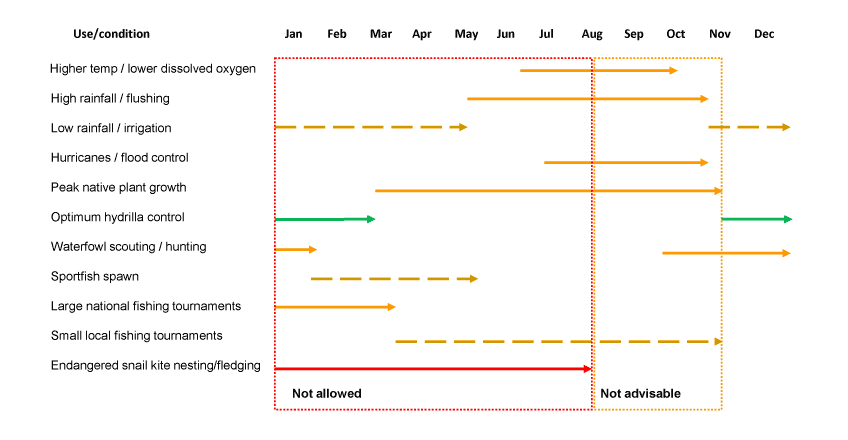

Not only is large-scale hydrilla management not advisable during snail kite nesting and peak juvenile kite foraging months…

CONSIDERATION: Endangered species

Large-scale hydrilla management is not allowed–especially around kite nesting and foraging areas. While direct herbicide toxicity to snail kites or apple snails is not an issue, there is concern that habitat loss (hydrilla control) and disturbance from airboats or helicopters applying herbicides may impact nesting and fledging success.

CONSIDERATION: Endangered species

This further reduces opportunities for large-scale hydrilla control.

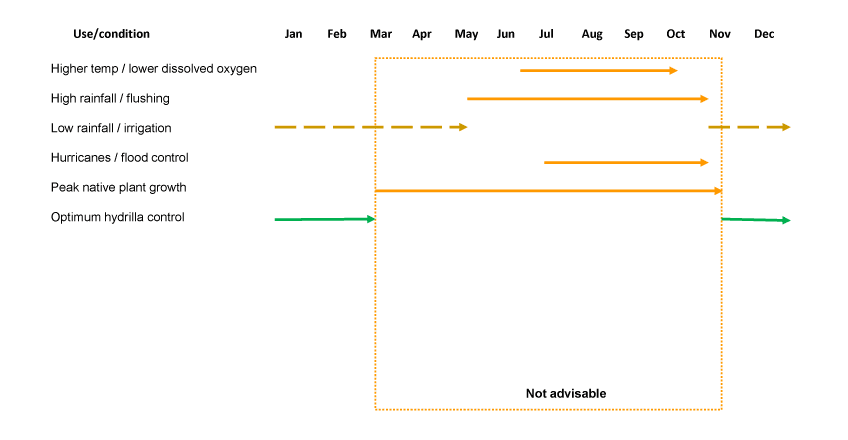

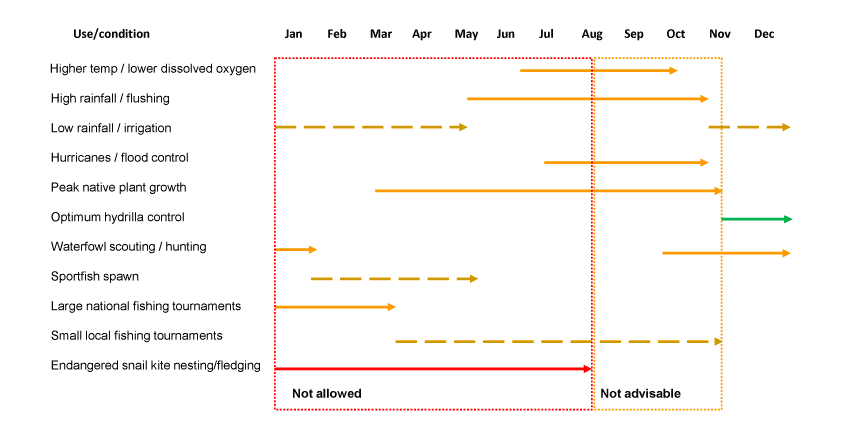

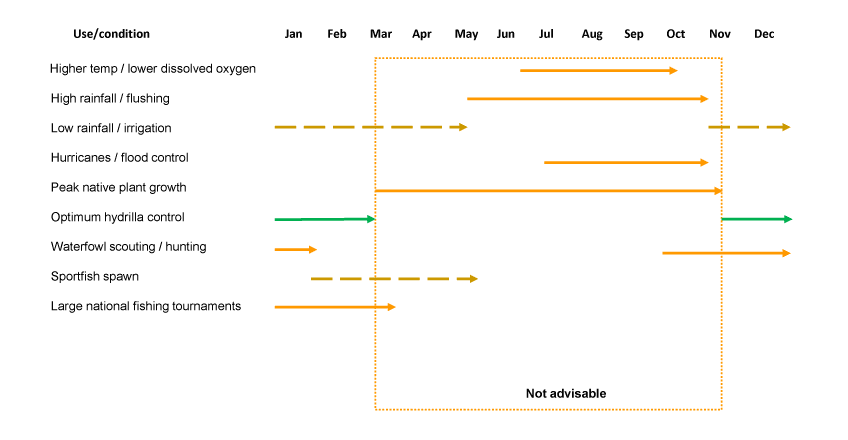

CONSIDERATION: Optimum control and overlapping uses

The “optimum” large-scale hydrilla management window now coincides with waterfowl hunting season on Lake Toho.

CONCLUSION

Plant managers are challenged to conduct large-scale hydrilla control on Lake Toho every year to protect and enhance native plant and wildlife communities, prevent flooding, and allow for year-round navigation while also coordinating their control efforts with dozens of user groups and seasonal events. What would you do?