Flood Control

Florida would be an entirely different state were it not for flood control. It has enabled Florida to become a top tourist destination, a popular spot for winter residents, a leading agricultural producer, and a place with thousands of waterfront homes.

During the land boom of the 1920s, developers saw the potential to transform south Florida's muggy swamps and wetlands into a hospitable paradise for people. All that was needed was to drain the expansive Everglades, keep the ground under future homes dry, and the fields for future crops adequately watered. This vision, coupled with deadly hurricanes and flooding in the late 1920s, started the drainage and control of south Florida's waters.

Florida's flat topography, heavy rainfall, and limestone bedrock combine to create land that is highly prone to flooding. Flooding occurs when the ground can't absorb heavy rains, and when natural waterways can't hold the excess water. These factors add up to 14.25 million acres (41%) of Florida's land being flood-prone, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

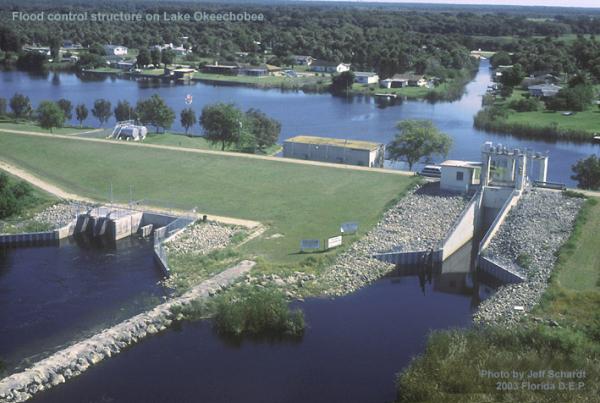

Flooding is a natural process. In floodplain ecosystems such as the Everglades, rainfall collects on the surface and drains into the soil, recharging the water supply of the underground aquifer. This is important because Florida relies almost completely on groundwater for drinking and domestic water-supply needs. Excessive flooding has caused death and economic losses throughout Florida's history. To facilitate drainage and to protect property and lives, environmental engineers devised a complex system of levees, canals, dams, reservoirs, pumping stations, and other water-control structures to manage fresh water and provide flood control in Florida.

Water control structures provide routes for excess water to drain into impoundment areas or into the ocean. Such devices also facilitate irrigation for Florida's agricultural crops, industries, and rapidly increasing residential populations. During the wet season (June-October), these water-control structures protect fields and urban areas from flooding. During the dry season (November-May), the structures supply water for drinking and irrigation.

Hasty development in the past has led to negative environmental effects today. The use of flood-control structures remains controversial in Florida, as conservationists clash with developers. Water-control devices must be clear of vegetation, to function properly. The need to consistently manage vegetation in canals adjacent to flood control structures in reservoirs and on rivers can conflict with the desires of anglers and waterfront property owners who may prefer the habitat and aesthetic value of plant communities.

Aquatic Plant Management and Flood Control

The unimpeded flow of water is necessary for canals to carry out their intended function of conveying water. For flood control structures to function properly and efficiently, they must remain free of obstructions such as aquatic plants.

Blocked canals hinder navigation, create water-supply problems, and prevent flood control. Dense growths of aquatic plants can block the water flow of drainage canals by as much as 95%, allowing only 5% of the intended water capacity to flow through the canal 1.3 million Floridians live in a flood-prone area, and need properly functioning water control structures during heavy rains and hurricanes. Agencies such as Florida’s five Water Management Districts, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and scores of local governments all share responsibilities for maintaining water-control structures. Plant management is an important aspect of this maintenance. Plant managers often rely on herbicide treatments to control aquatic plants such as hydrilla. Mechanical control methods are also used to clear away aquatic plants.